|

Early Lake St. Clair: Geologists find Lake St. Clair's beginnings in the glacial eras. The prehistoric lake covered all of Grosse Pointe except for terrain that is now The Hill in Grosse Pointe Farms. The crest of this island stretched along the present Kercheval Avenue and Ridge Road. Over time, as the lake drained into an evolving Detroit River, the island expanded. Eventually, its northern beach which stretched along Mack Avenue from East Outer Drive to Eleven Mile Road served, in turn, as an Indian pathway, a French settler road and a Grosse Pointe thoroughfare. Early Lake St. Clair: Geologists find Lake St. Clair's beginnings in the glacial eras. The prehistoric lake covered all of Grosse Pointe except for terrain that is now The Hill in Grosse Pointe Farms. The crest of this island stretched along the present Kercheval Avenue and Ridge Road. Over time, as the lake drained into an evolving Detroit River, the island expanded. Eventually, its northern beach which stretched along Mack Avenue from East Outer Drive to Eleven Mile Road served, in turn, as an Indian pathway, a French settler road and a Grosse Pointe thoroughfare.

Early Visitors: Animals and people arrived in Southeastern Michigan between glacial advances. Paleo-Indians, like their descendants, used Lake St. Clair beaches for hunting and trading. Arrow heads and pottery shards left behind have been uncovered by amateur archeologists like Jerry De Visscher, who, as a boy, found many artifacts near Mack Avenue on his father's Cook Road farm.

In historical times, the Native Americans were joined by European missionaries and illegal traders/trappers or coureurs de bois. In summer 1669, the Frenchman Adrien Joliet, with his Iroquois guide, was among the first white men to venture into Lake St. Clair. Aboard the Griffin a decade later on August 12th, the Feast Day of Ste. Claire of Assisi, Robert Cavalier de la Salle entered the waterway; his chaplain, Father Hennepin, named the lake for that saint. Soon, licensed Montreal fur traders appeared gliding near the lake shore in canoe flotillas paddled by hired voyageurs.

Cadillac’s Village: Antoine Laumet de la Mothe Cadillac, who had lived in Canada since 1683, was named Commandant of Fort Michilimackinac in 1694. There, he prospered in the fur trade, but antagonized the Jesuits by selling liquor to the Indians.

After the "western" forts closed in 1696, Cadillac obtained Louis XIV’s permission to establish a post on the lower Great Lakes. In spring 1701, he embarked from Montreal with 100 men. On July 23rd this band traversed Lake St. Clair and after visiting Grosse Ile, landed the next day just west of Hart Plaza. As ordered, Cadillac named the site Fort Pontchartrain after the French Minister of the Marine. To promote the fur trade, he invited Indian tribes including the Miami, Huron, Chippewa (Ojibway), Ottawa and eventually Potawatomi, to settle near the fort. By 1710 when he departed to become Governor of Louisiana, settlers occupied land well beyond the stockade. However, no permanent inhabitants would live in Grosse Pointe for another forty years.

The Fox Indian Episode: Grosse Pointe first acquired historic significance in 1712. That summer more than a thousand Fox, Saulk and Mascoutin Indians came to Fort Pontchartrain from Wisconsin. Unhappy with their reception, they laid siege to the village. The French routed the visitors with the help of friendly braves who returned from summer raids along the Mississippi, and pursued them to marshy Grosse Pointe, later referred to as Windmill Pointe. After a four day battle, about a hundred of the intruders escaped to Wisconsin. In later years, tribal elders came to see where their families had died. Local people found Indian relics on the high ground, and a nearby stream became known as Fox Creek. Today, a plaque on the median of Windmill Pointe Drive commemorates the battle.

Life in the 1700s: Initially there was little to encourage Grosse Pointe settlements especially since a grand marais, or great marsh, stretched from Waterworks Park to Bishop Road. Then, the French king, Louis XV, concerned about English incursions into the Ohio Valley, offered new incentives to attract colonists like Grosse Pointe's earliest pioneers, the Trombleys and LaForests. Coming from French Canada in 1750, the Trombleys became the area's first habitants or farmers, and LaForest became the manager of the LeDuc grist mill on Windmill Pointe. They were soon joined by the Fretons, Deshetres, and Duchenes. Each family had a narrow plot of land, often three miles in depth. These tracts, nicknamed ribbon farms, provided access to the lake for drinking water, fishing and transportation, to the shore for fields and cabins and to the forest for timber and game.

According to habitant folklore, suspicious settlers saw the feu follet, or sprite, in low-lying fogs. They marked horses with Christian crosses to protect against le lutin, a hard-driving, horned nightrider. They told of youthful Archange pursued by the loup garou, a wolf-headed monster with a long tail. They recited the legend of the LeDuc grist mill. When Josette LeDuc became ill, her co-owner and younger brother, Jean Baptiste, asked once too often about her share in the mill. Annoyed, Josette responded, "Oh, leave it to the devil!" During a great storm as she breathed her last, lightening split the building rendering it useless. Thereafter, in bad weather, habitants looked skyward expecting the devil's arrival to claim his bequest.

British Control: Grosse Pointe farmers of the 1750s would have been aware of the English westward incursions that would result in war and bring an end  to French control of Fort Pontchartrain. Indeed, the region, though escaping attack, was occupied by the British under Major Robert Rogers on November 29, 1760. The new government required an oath of allegiance, but generally treated habitants fairly. Nevertheless, some French villagers, uneasy among British military and English-speaking businessmen, moved to Grosse Pointe. to French control of Fort Pontchartrain. Indeed, the region, though escaping attack, was occupied by the British under Major Robert Rogers on November 29, 1760. The new government required an oath of allegiance, but generally treated habitants fairly. Nevertheless, some French villagers, uneasy among British military and English-speaking businessmen, moved to Grosse Pointe.

Habitant Grosse Pointe: New families, including the Patenaudes, Morans, Rivards and Gouins, established farms along the shore. They cultivated fields near the water and planted fenced kitchen gardens beside their cabins. They allowed their livestock to roam free. The pride of many farms were the orchards of legendary French pear trees. Still found in Grosse Pointe today, some are as tall as oaks.

Habitant customs reflected traditional French Canadian culture. The New Year's masked Ignolee solicited gifts for the poor, and the mid-winter Marti Gras provided festive diversions before the strictness of Lent. Canoes were indispensable for travel. Charrettes (carts) and carrioles (sleighs) were often used for races behind swift ponies. The Fort remained a primary source of supplies, refuge, vital news and religious celebration. Frequently, after Catholic services at St. Anne’s, the fort's only church, habitants sold their produce to villagers - a practice considered scandalous by later Protestant arrivals.

Chief Pontiac’s War (1763): By adapting to the native way of life, early habitants gained the Native Americans' respect. Though sometimes asking for a meal or a place by the fire, members of the Algonquin tribes usually remained good neighbors. Only the Hurons crossed the ice from Canada to drive off habitant livestock.

After 1762, however, unrest increased, causing fewer families to homestead in Grosse Pointe. The British had limited the goods traded to Native Americans, not even allowing them enough ammunition to hunt for food. Anxious braves, united under Ottawa Chief Pontiac, laid siege to the Fort in May 1763. They won the major Battle of Bloody Run at Parent's Creek on July 31st. But instead of following up on their victory, by December the tribes began to seek peace. Thus, Detroit became the only western post never held by the Indians. After 1762, however, unrest increased, causing fewer families to homestead in Grosse Pointe. The British had limited the goods traded to Native Americans, not even allowing them enough ammunition to hunt for food. Anxious braves, united under Ottawa Chief Pontiac, laid siege to the Fort in May 1763. They won the major Battle of Bloody Run at Parent's Creek on July 31st. But instead of following up on their victory, by December the tribes began to seek peace. Thus, Detroit became the only western post never held by the Indians.

During the hostilities, French settlers, previously supportive of the Indians, grew ambivalent. Some habitants pleaded with the Chief to make peace while others smuggled necessities into the Fort. But, when certain settlers openly encouraged the natives, Fort commander Major Gladwin labeled them "the scoundrel inhabitants of Detroit."

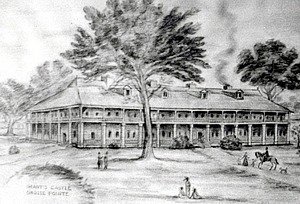

The Revolutionary War: In the 1770s, families of Scottish or Irish origin joined French habitants in Grosse Pointe. Alexander Grant, a British Great Lakes naval commander, built his home and headquarters - the area’s first mansion later called Grant's Castle - at Moran and Lake Shore Road.  Along the lake from there to Provencal Road, the Forsyth family of traders acquired several contiguous ribbon farms. During the Revolutionary War, they, like all Grosse Pointers, had to contribute part of their meager stores, even in the severe winter of 1779-1780, to the war effort when Detroit became a major British supply center under Lt. Col. Henry Hamilton. Along the lake from there to Provencal Road, the Forsyth family of traders acquired several contiguous ribbon farms. During the Revolutionary War, they, like all Grosse Pointers, had to contribute part of their meager stores, even in the severe winter of 1779-1780, to the war effort when Detroit became a major British supply center under Lt. Col. Henry Hamilton.

Though made part of the United States by the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Detroit remained under British control for another thirteen years. Not until the 1794 Jay Treaty, did General Anthony Wayne's victories over the English enable the Americans to claim their possession. On July 11, 1796, Capt. Moses Porter exchanged the Union Jack for the Stars and Stripes, thus incorporating Michigan into the Northwest Territory.

A Third Flag for Detroit: Americans found the situation around Detroit delicate, given its inhabitants' diverse expectations and Canada's close proximity. For English loyalists, relocating across the river was always an option. While Wayne County, initially larger than the state in which it is found, was created in 1796, the Territory of Michigan was not established until June 30, 1805.  Detroit had burned to the ground nineteen days before, and during its rebuilding, city residents sought refuge with farmers in areas like Grosse Pointe. American newcomers, having little patience with French informality, possibly coined the term, "muskrat French" at this time. Detroit had burned to the ground nineteen days before, and during its rebuilding, city residents sought refuge with farmers in areas like Grosse Pointe. American newcomers, having little patience with French informality, possibly coined the term, "muskrat French" at this time.

Because of confusion over previous Indian, French and British land grants, the U.S. Congress now passed several Acts relating to property ownership. Between 1808 and 1812, Grosse Pointers visited the Detroit Land Office to document their holdings. If able to establish possession, they received United States Land Patents and Private Claim (P.C.) Numbers.

|